Having only been performed twice in its original form in the UK, in 1907 and 2010, a new version of Oscar Wilde’s The Duchess of Padua will be the first operatic adaptation of the work to be presented in Europe.

An intimate Italian-style opera with arias, ensembles, a love-duet, and a death scene, The Duchess of Padua features four voices and a piano duo who together bring Wilde’s epic tragedy of revenge and passion to life. The work tells the story of an earnest young man who falls for the oppressed wife of a cruel and coercive Duke and the tragic consequences that follow. The melodramatic and sentimental this adaptation features music by Edward Lambert, founder of The Music Troupe.

The production is directed by Fleur Snow, currently Staff Director at Theater St Gallen, Switzerland and whose credits include Opera Holland Park and Welsh National Opera and features soprano Ellie Neate, mezzo-soprano Anna Elizabeth Cooper, tenor James Beddoe and bass Henry Grant Kerswell.

Lambert has written 18 chamber operas during his career including Caedmon (Royal Opera / Donmar Warehouse), The Button Moulder (Royal Opera Education), All in the Mind, (W11 Opera / Britten Theatre) and Six Characters in Search of a Stage (2014 Brighton Fringe and London venues).

We caught up with Lambert ahead of opening The Duchess of Padua to find out more.

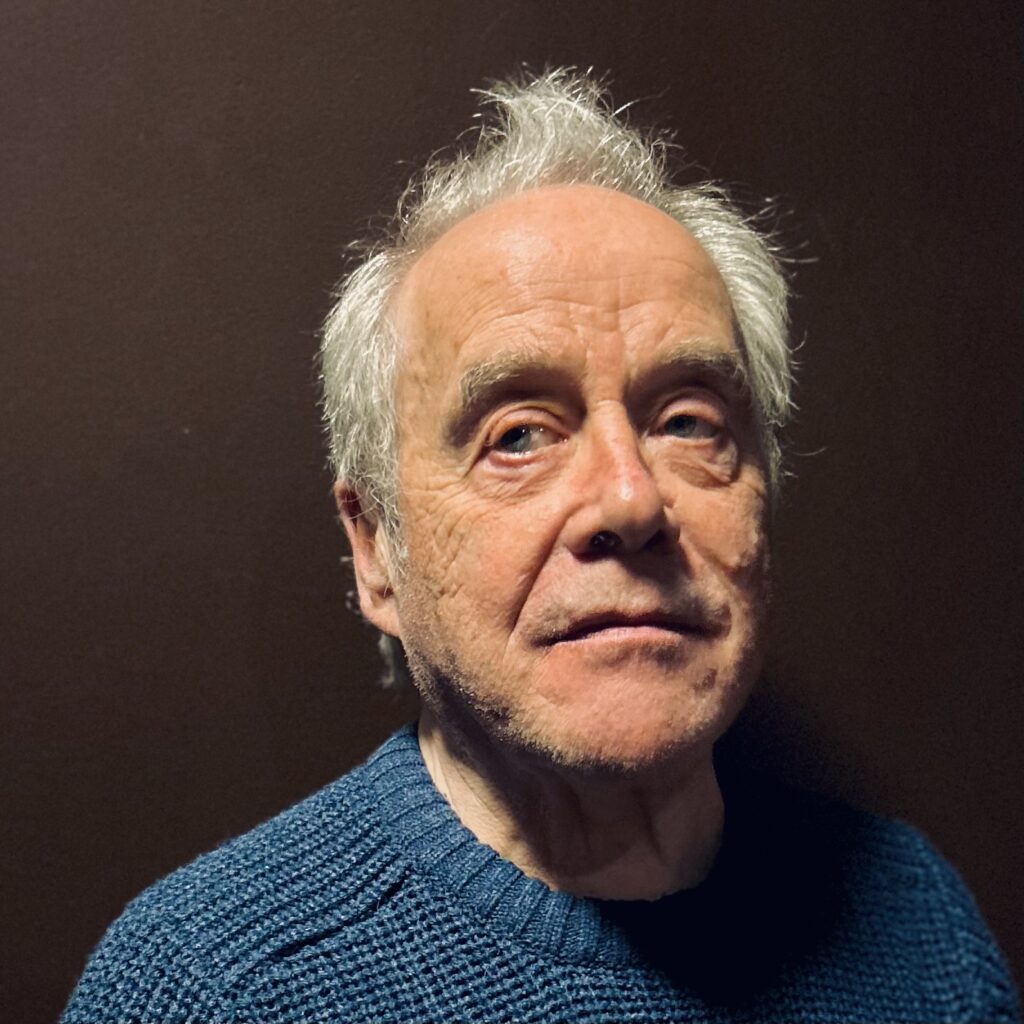

Q&A with Edward Lambert

When did you first become aware of The Duchess of Padua and what was it about the work that drew you to adapting it for chamber opera?

My particular joy in writing chamber operas is to show off the qualities of the voice. Classically trained opera singers have amazing talents – the beauty, individuality and agility of the sound they make, their dramatic skills and their musicianship. Since opera emanated from Italy and the repertory of its Golden Age was almost exclusively Italian, I was looking for an Italian subject which would complement my vocal style, which is a sort-of modern remake of ‘bel canto’. At the same time, Italian opera took its texts very seriously and libretti were typically crafted by serious literary figures. I chanced upon The Duchess of Padua by Oscar Wilde and thought these things might come together.

What can you tell us about the story Wilde’s play tells?

Wilde’s mother was not only a poet, but an advocate for women’s rights. He himself was to edit The Women’s World magazine for a while. A definite feminist strain emerges in the character of the Duchess. She’s trapped in a loveless marriage and her cruel husband subjects her to coercive control. When she falls for a passionate but high-minded young man, she contemplates suicide as a release from her situation, but kills her husband instead. Unfortunately, when her horrified lover rejects her, she blames the murder on him and the tragedy of the final act ensues. These situations may smack of melodrama but then this play was written in the heyday of Victorian Gothic. Besides, remembering the successful appeal of Sally Challen in 2019 against a murder conviction on the grounds that she was a victim of domestic abuse, the Duchess is a complex character we can recognise and sympathise with.

How did you approach devising the adaptation?

Alas, I’m no scholar of Oscar Wilde, but it appears the play is usually dismissed as derivative, quoting sources as varied as Shakespeare, Jacobean tragedy, Victor Hugo (Lucrezia Borgia), and Shelley (I Cenci). I would have thought that the literary quality of the text, which is written in elevated blank verse, stands comparison with these mighty figures. However, the play feels over long and contains many subsidiary parts and background ‘chatter’ so, at the least, it seems prohibitively unwieldy to produce. Hence, perhaps, its neglect. Yet, although some of the text might be over-sentimental when spoken, it would, I reckoned, be suitable for singing. Since the opera had to be economical in scale, I began by cutting those small parts and reducing the quantity of text. I cut the entire fourth act (there are five in the play). I was left with a much more personal drama for just four characters which, I supposed, from a dramatic point of view, would work well. Arrogant as it must seem, I’ve persuaded myself that Wilde wouldn’t turn in his grave if he saw the result. Finally, I decided to write the accompaniment for piano duet since I was reminded that playing duets – one piano, four hands – was a favourite from of Victorian domestic entertainment.

Has the work changed from your original vision for it?

Since our productions have, by their very nature, to be simple and tailored for small spaces, I needed to find a way of suggesting the epic nature of the settings: the market square of Padua in front of the cathedral, the Duke’s palace, the Duke’s bedchamber and the dungeon of the castle. I was struck by the details and eloquence of Wilde’s stage directions and it occurred to me to include these as part of the sung text. Our four singers therefore double as a chorus describing the scene, commenting on the action or even taking over lines from the main characters. When the Duchess and Guido fall in love, for example, the other cast members join in and together they sing a ‘madrigal’. It’s all Wilde’s text in its original sequence, but re-purposed from time to time in different ways. The opera’s therefore meant to be highly stylised, frequently stepping outside the drama and doing a bit of storytelling.

How does it feel to be opening the opera at The Space Theatre before touring the show?

In many ways, it’s great to be showcasing this work away from the glare of the West End (chance would be a fine thing!) The Space Theatre, in a converted church on the Isle of Dogs, was set up to support new writing and, indeed, the team there could hardly be more encouraging and helpful. We don’t have the resources of manpower or money to mount ambitious productions and we want to show that an opera company doesn’t have to have much infrastructure. Besides, The Space boasts lovely acoustics and a Steinway grand piano. Our mini tour is designed to try out the work in four very different types of venue down to a village hall.

Is there anything you hope audiences take away from the show?

”Personally I like comedy to be intensely modern, and like my tragedy…. to be remote”, Wilde wrote. The play is a product of the Aesthetic Movement – the Cult of Beauty – whose arts and crafts were inspired by the past but very much of their time. I admire the products of this period and hope people will similarly enjoy the combination of beautiful voices and Wilde’s drama which I hope my opera offers. As I write, the cast is working hard to master roles which are incredibly challenging: I want my audiences to be amazed by their performances. Isn’t that the wonder of opera, the combination of so many talents?

The Duchess of Padua is at The Space Theatre, London from 20 to 25 February